Readings:

Psalm 104:17-25

Prayer of Azariah 52-59

Revelation 22:1-5

Luke 8:22-25[Common of a Prophetic Witness]

[Common of a Scientist or Environmentalist]

[For the Care of God's Creation]

[For the Goodness of God's Creation]Preface of a Saint (3)

PRAYER (traditional language)

Blessed Creator of the earth and all that inhabits it: We offer thanks

for thy prophets John Muir and Hudson Stuck, who rejoiced in your beauty

made known in the natural world; and we pray that, inspired by their love

of thy creation, we may be wise and faithful stewards of the world thou

hast created, that generations to come may also lie down to rest among

the pines and rise refreshed for their work; in the Name of the one through

whom all things art made new, Jesus Christ our Savior, who with thee and

the Holy Spirit livest and reignest, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

PRAYER (contemporary language)

Blessed Creator of the earth and all that inhabits it: We thank you for

your prophets John Muir and Hudson Stuck, who rejoiced in your beauty

made known in the natural world; and we pray that, inspired by their love

of your creation, we may be wise and faithful stewards of the world you

have created, that generations to come may also lie down to rest among

the pines and rise refreshed for their work; in the Name of the one through

whom you make all things new, Jesus Christ our Savior, who with you and

the Holy Spirit lives and reigns, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

This commemoration appears in A Great Cloud of Witnesses.

Return to Lectionary Home Page

Webmaster: Charles Wohlers

Last updated: 20 Feb. 2021

JOHN MUIR and HUDSON STUCK

NATURALIST & WRITER, 1914;

PRIEST & ENVIRONMENTALIST, 1920

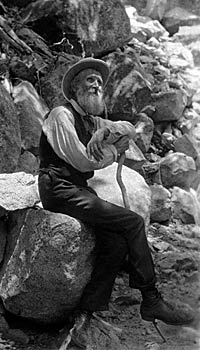

John

Muir (21 April 1838 – 24 December 1914) was a Scottish-born

American naturalist, author, and early advocate of preservation of wilderness

in the United States. His letters, essays, and books telling of his adventures

in nature, especially in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, have

been read by millions. His activism helped to save the Yosemite Valley,

Sequoia National Park and other wilderness areas. The Sierra Club, which

he founded, is now one of the most important conservation organizations

in the United States.

John

Muir (21 April 1838 – 24 December 1914) was a Scottish-born

American naturalist, author, and early advocate of preservation of wilderness

in the United States. His letters, essays, and books telling of his adventures

in nature, especially in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, have

been read by millions. His activism helped to save the Yosemite Valley,

Sequoia National Park and other wilderness areas. The Sierra Club, which

he founded, is now one of the most important conservation organizations

in the United States.

In his later life, Muir devoted most of his time to the preservation of the Western forests. He petitioned the U.S. Congress for the National Park Bill that was passed in 1899, establishing both Yosemite and Sequoia National Parks. Because of the spiritual quality and enthusiasm toward nature expressed in his writings, he was able to inspire readers, including presidents and congressmen, to take action to help preserve large nature areas.

Muir's biographer, Steven Holmes, states that Muir has become "one of the patron saints of twentieth-century American environmental activity," both political and recreational. "Muir has profoundly shaped the very categories through which Americans understand and envision their relationships with the natural world," writes Holmes. Muir was noted for being an ecological thinker, political spokesman, and religious prophet, whose writings became a personal guide into nature for countless individuals, making his name "almost ubiquitous" in the modern environmental consciousness. According to author William Anderson, Muir exemplified "the archetype of our oneness with the earth."

John Muir was born in Dunbar, East Lothian, Scotland to Daniel Muir and Ann Gilrye. In 1849, Muir's family emigrated to the United States, starting a farm near Portage, Wisconsin. Stephen Fox recounts that Muir's father found the Church of Scotland insufficiently strict in faith and practice, leading to their emigration and joining a congregation of the Campbellite Restoration Movement. By age 11, young Muir had learned to recite "by heart and by sore flesh" all of the New Testament and most of the Old Testament. But in maturity, Muir was never confused by orthodox beliefs. In a letter to his fond friend Emily Pelton, dated 23 May 1865, he wrote, "I never tried to abandon creeds or code of civilization; they went away of their own accord... without leaving any consciousness of loss." Muir remained, though, a deeply religious man, writing, "We all flow from one fountain—Soul. All are expressions of one love. God does not appear, and flow out, only from narrow chinks and round bored wells here and there in favored races and places, but He flows in grand undivided currents, shoreless and boundless over creeds and forms and all kinds of civilizations and peoples and beasts, saturating all and fountainizing all."

He attended the Univ. of Wisconsin but never graduated, spent most of the Civil War in Canada (possibly to avoid the draft), and, after the war, returned to the United States to work as an industrial engineer in Indianapolis. An accident there caused him to leave; he would later write: "God has to nearly kill us sometimes, to teach us lessons." From that point on, he determined to "be true to myself" and follow his dream of exploration and study of plants.

In September 1867, Muir undertook a walk of about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from Indiana to Florida, which he recounted in his book A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf. After reaching Florida, he sailed to New York and booked passage to California.

Arriving in San Francisco in March 1868, Muir immediately left for a week-long visit to Yosemite, a place he had only read about. Seeing it for the first time, a biographer notes that "he was overwhelmed by the landscape, scrambling down steep cliff faces to get a closer look at the waterfalls, whooping and howling at the vistas, jumping tirelessly from flower to flower."[7] "We are now in the mountains and they are in us, kindling enthusiasm, making every nerve quiver, filling every pore and cell of us," Muir later wrote. . . . "No temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite... The grandest of all special temples of Nature." He lived in a cabin there for two years, and wrote about this period in his book First Summer in the Sierra (1911). Muir biographer Frederick Turner notes Muir's journal entry upon first visiting the valley and writes that his description "blazes from the page with the authentic force of a conversion experience."

Yosemite Valley

(photo by web author)

Pursuit of his love of science, especially geology, often occupied his free time. Muir soon became convinced that glaciers had sculpted many of the features of the valley and surrounding area. This notion was in stark contradiction to the accepted contemporary theory, promulgated by Josiah Whitney (head of the California Geological Survey), which attributed the formation of the valley to a catastrophic earthquake. Muir was eventually proved correct.

Muir threw himself into the preservationist role with great vigor. He envisioned the Yosemite area and the Sierra as pristine lands. He saw the greatest threat to the Yosemite area and the Sierra to be livestock, especially domestic sheep, calling them "hoofed locusts." On 30 September 1890, the U.S. Congress passed a bill that essentially followed recommendations that Muir had suggested in two articles in Century magazine, The Treasure of the Yosemite and Features of the Proposed National Park, both published in 1890. But to Muir's dismay, the bill left Yosemite Valley under state control, as it had been since the 1860s.

In early 1892, Professor Henry Senger, a philologist at the University of California, Berkeley contacted Muir with the idea of forming a local 'alpine club' for mountain lovers. Senger and San Francisco attorney Warren Olney sent out invitations "for the purpose of forming a 'Sierra Club.' Mr. John Muir will preside." On May 28, 1892, the first meeting of the Sierra Club was held to write articles of incorporation. One week later Muir was elected president.

Historian Dennis Williams notes that Muir's philosophy and world view rotated around his perceived dichotomy between civilization and nature. From this developed his core belief that "wild is superior". His nature writings became a "synthesis of natural theology" with scripture that helped him understand the origins of the natural world. He came to believe that God was always active in the creation of life and thereby kept the natural order of the world. As a result, Muir "styled himself as a John the Baptist," adds Williams, "whose duty was to immerse in 'mountain baptism' everyone he could." Williams concludes that Muir saw nature as a great teacher, "revealing the mind of God," and this belief became the central theme of his later journeys and the "subtext" of his nature writing.

The high peaks of Yosemite

(Photo by web author)

During his career as writer and while living in the mountains, Muir continued to experience the "presence of the the divine in nature," writes Holmes. From Travels in Alaska: "Every particle of rock or water or air has God by its side leading it the way it should go; The clearest way into the Universe is through a forest wilderness; In God's wildness is the hope of the world." His personal letters also conveyed these feelings of ecstasy. Historian Catherine Albanese stated that in one of his letters, "Muir's eucharist made Thoreau's feast on wood-chuck and huckleberry seem almost anemic." She added that "Muir had successfully taken biblical language and inverted it to proclaim the passion of attachment, not to a supernatural world but to a natural one. To go to the mountains and sequoia forests, for Muir, was to engage in religious worship of utter seriousness and dedication." She quotes Muir's letter: Do behold the King in his glory, King Sequoia. Behold! Behold! seems all I can say. Some time ago I left all for Sequoia: have been and am at his feet fasting and praying for light, for is he not the greatest light in the woods; in the world."

During his lifetime John Muir published over 300 articles and 12 books. Muir has been called the "patron saint of the American wilderness" and its "archetypal free spirit." Author Gretel Ehrlich states that as a "dreamer and activist, his eloquent words changed the way Americans saw their mountains, forests, seashores, and deserts." He not only led the efforts to protect forest areas and have some designated as national parks, but his writings gave readers a conception of the relationship between "human culture and wild nature as one of humility and respect for all life," writes author Thurman Wilkins. His friend Henry Fairfield Osborn noted that he retained from his early religious training under his father "this belief, which is so strongly expressed in the Old Testament, that all the works of nature are directly the work of God."

— more at Wikipedia

Hudson

Stuck (November 11, 1863 – October 10, 1920) was an Episcopal

priest who is best known for co-leading the first expedition to successfully

climb Mount McKinley (Denali). He was also a social reformer, both in

Texas and Alaska.

Hudson

Stuck (November 11, 1863 – October 10, 1920) was an Episcopal

priest who is best known for co-leading the first expedition to successfully

climb Mount McKinley (Denali). He was also a social reformer, both in

Texas and Alaska.

Stuck was born in London and graduated from King's College London. He then moved to Texas, graduated from Sewanee and was ordained a priest in 1892. From 1896 to 1904 he served as Dean of St. Matthew's Cathedral in Dallas. There he was active in social reforms, condemning lynching, and working for gun control and expansion of recreational areas. He also founded a night school for millworkers and was instrumental in having one of Texas' first child labor laws passed.

In 1904, looking for more challenges, he moved to Alaska, becoming Archdeacon of the Yukon and the Arctic. There he worked for the benefit of Indians and Eskimos, but became most famous for organizing and co-leading the first successful ascent of Mt. McKinley (Denali) in 1913.

He wrote of his work in Alaska in several books, including Ten

Thousand Miles with a Dog Sled: A Narrative of Winter Travel in Interior

Alaska, Ascent

of Denali and The

Alaskan Missions of the Episcopal Church : a Brief Sketch, Historical

and Descriptive.