Readings:

1 Kings 17:2-6

Psalm 4:1-5

Philippians 2:12-18

Luke 14:27-33Preface of a Saint (2)

[Common of a Monastic or Professed Religious]

[Common of a Theologian]

[Of the Holy Spirit]

[Of the Incarnation]

[For the Ministry III]

PRAYER (traditional language)

Gracious God, whose service is perfect freedom and in whose commandments there is nothing harsh nor burdensome: Grant that we, with thy servant Benedict, may listen with attentive minds, pray with fervent hearts, and serve thee with willing hands, so that we live at peace with one another and in obedience to thy Word, Jesus Christ our Lord, who with thee and the Holy Ghost liveth and reigneth, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

PRAYER (contemporary language)

Gracious God, whose service is perfect freedom and in whose commandments there is nothing harsh nor burdensome: Grant that we, with your servant Benedict, may listen with attentive minds, pray with fervent hearts, and serve you with willing hands, so that we live at peace with one another and in obedience to your Word, Jesus Christ our Lord, who with you and the Holy Spirit lives and reigns, one God, now and for ever. Amen.

Lessons revised in Lesser Feasts & Fasts 2024.

March 21 is an alternate date for this commemoration.

Return to Lectionary Home Page

Webmaster: Charles Wohlers

Last updated: 9 July 2024

BENEDICT

FOUNDER OF WESTERN MONASTICISM (11 JULY 540)

Benedict was born at Nursia (Norcia) in Umbria, Italy, around 480 AD.

He was sent to Rome for his studies, but was repelled by the dissolute

life of most of the populace, and withdrew to a solitary life at Subiaco.

A group of monks asked him to be their abbot, but some of them found his

rule too strict, and he returned alone to Subiaco. Again, other monks

called him to be their abbot, and he agreed, founding twelve communities

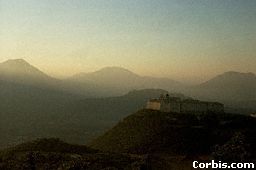

over an interval of some years. His chief founding was Monte Cassino,

an abbey which stands to this day as the mother house of the world-wide

Benedictine order.

Totila

the Goth visited Benedict, and was so awed by his presence that he fell

on his face before him. Benedict raised him from the ground and rebuked

him for his cruelty, telling him that it was time that his iniquities

should cease. Totila asked Benedict to remember him in his prayers and

departed, to exhibit from that time an astonishing clemency and chivalry

in his treatment of conquered peoples.

Totila

the Goth visited Benedict, and was so awed by his presence that he fell

on his face before him. Benedict raised him from the ground and rebuked

him for his cruelty, telling him that it was time that his iniquities

should cease. Totila asked Benedict to remember him in his prayers and

departed, to exhibit from that time an astonishing clemency and chivalry

in his treatment of conquered peoples.

Benedict drew up a rule of life for monastics, a rule which he calls "a school of the Lord's service, in which we hope to order nothing harsh or rigorous." The Rule gives instructions for how the monastic community is to be organized, and how the monks are to spend their time. An average day includes about four hours to be spent in liturgical prayer (called the Divinum Officium -- the Divine Office), five hours in spiritual reading and study, six hours of labor, one hour for eating, and about eight hours for sleep. The Book of Psalms is to be recited in its entirety every week as a part of the Office.

A Benedictine monk takes vows of "obedience, stability, and conversion of life." That is, he vows to live in accordance with the Benedictine Rule, not to leave his community without grave cause, and to seek to follow the teaching and example of Christ in all things. Normal procedure today for a prospective monk is to spend a week or more at the monastery as a visitor. He then applies as a postulant, and agrees not to leave for six months without the consent of the Abbot. (During that time, he may suspect that he has made a mistake, and the abbot may say, "Yes, I think you have. Go in peace." Alternately, he may say, "It is normal to have jitters at this stage. I urge you to stick it out a while longer and see whether they go away." Many postulants leave before the six months are up.) After six months, he may leave or become a novice, with vows for one year. After the year, he may leave or take vows for three more years. After three years, he may leave, take life vows, or take vows for a second three years. After that, a third three years. After that, he must leave or take life vows (fish or cut bait). Thus, he takes life vows after four and a half to ten and a half years in the monastery. At any point in the proceedings at which he has the option of leaving, the community has the option of dismissing him.

The

effect of the monastic movement, both of the Benedictine order and of

similar orders that grew out of it, has been enormous. We owe the preservation

of the Holy Scriptures and other ancient writings in large measure to

the patience and diligence of monastic scribes. In purely secular terms,

their contribution was considerable. In Benedict's time, the chief source

of power was muscle, whether human or animal. Ancient scholars apparently

did not worry about labor-saving devices. The labor could always be done

by oxen or slaves. But monks were both scholars and workers. A monk, after

spending a few hours doing some laborious task by hand, was likely to

think, "There must be a better way of doing this." The result was the

systematic development of windmills and water wheels for grinding grain,

sawing wood, pumping water, and so on. The rotation of crops (including

legumes) and other agricultural advances were also originated or promoted

by monastic farms. The monks, by their example, taught the dignity of

labor and the importance of order and planning. For details, see The

Mediaeval Machine: The Industrial

Revolution of the Middle Age, by Jean Gimpel, (Holt Rinehart

& Winston, 1976; Penguin, 1977, ISBN 0-14-00-4514-7).

The

effect of the monastic movement, both of the Benedictine order and of

similar orders that grew out of it, has been enormous. We owe the preservation

of the Holy Scriptures and other ancient writings in large measure to

the patience and diligence of monastic scribes. In purely secular terms,

their contribution was considerable. In Benedict's time, the chief source

of power was muscle, whether human or animal. Ancient scholars apparently

did not worry about labor-saving devices. The labor could always be done

by oxen or slaves. But monks were both scholars and workers. A monk, after

spending a few hours doing some laborious task by hand, was likely to

think, "There must be a better way of doing this." The result was the

systematic development of windmills and water wheels for grinding grain,

sawing wood, pumping water, and so on. The rotation of crops (including

legumes) and other agricultural advances were also originated or promoted

by monastic farms. The monks, by their example, taught the dignity of

labor and the importance of order and planning. For details, see The

Mediaeval Machine: The Industrial

Revolution of the Middle Age, by Jean Gimpel, (Holt Rinehart

& Winston, 1976; Penguin, 1977, ISBN 0-14-00-4514-7).

by James Kiefer